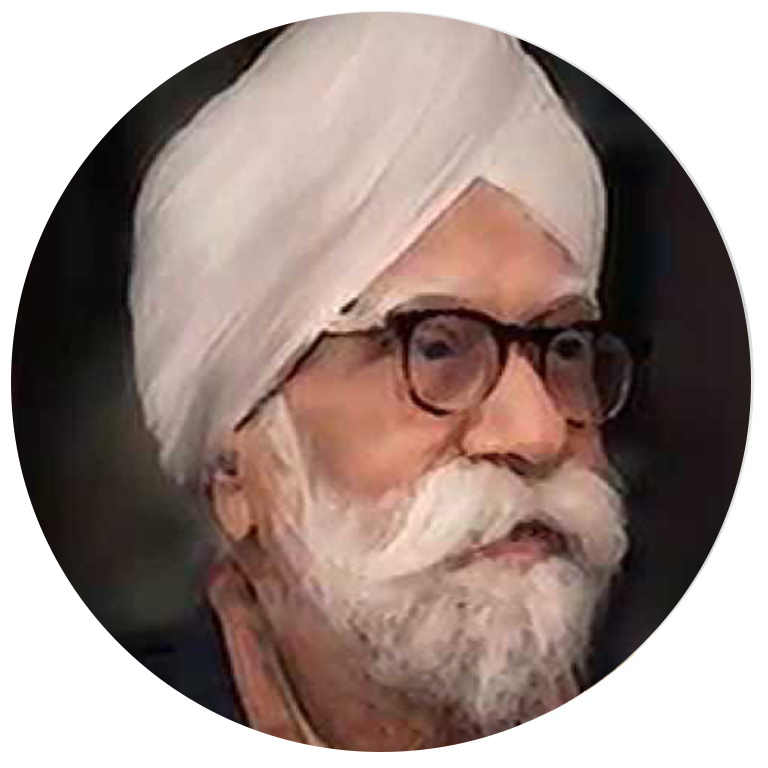

Gian Singh Naqqash, who painted the interiors of the Golden Temple, died in poverty

but four generations after him have nevertheless devoted themselves to

embellishing Sikh art, writes Varinder Walia (The Tribune)

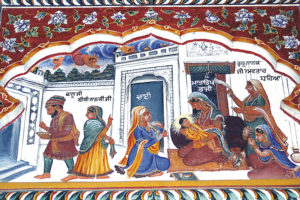

Imagine a revered Sikh naqqash, who painted frescos on the walls of the Harmander Sahib, including the dome of the structure with indigenously prepared colours for more than three decades, died in penury in 1953 at the age of 70. He was then selling clay toys painted with the same brush. This unsung artist was Gian Singh, the master naqqash. He was a painter of frescos, the art of transferring the outline of a design on wet plaster and then filling it with suitable colours before it dries up.

No Sikh organisation had come to the rescue of the renowned artist during his lifetime. Of course, Naqqash was honoured by the SGPC in 1949, but no financial help came from any quarter till his death.

Gian Singh Naqqash is remembered for giving originality to Sikh art by introducing many innovations in frescoes like Dehin, the most captivating item of fresco painting. Dehin has been executed by him in the sanctum sanctorum, just above Har ki Pauri. It bears testimony to the incomparable workmanship of this artist.

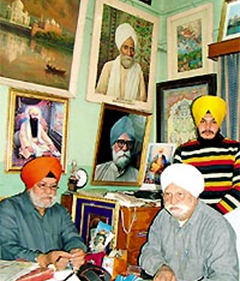

While some Sikh institutions are responsible for destroying invaluable Sikh heritage in the name of ‘kar seva’, the contribution of the family of Gian Singh Naqqash to the Sikh School of Art is immense. His son, G.S. Sohan Singh Artist, and grandsons, Satpal Singh Danish and Surinder Singh, and great grandson, Hardip Singh, have been in the field of Sikh art. There is hardly any family, other than this, which has served Sikh art for five generations. But still for the Naqqash family, the wheel of life has been moving surely on the road to art despite negligible recognition from Sikh organisations.

The great grandson of Gian Singh Naqqash, Hardip Singh, is busy these days in preserving the invaluable artwork of his father, grandfather and great grandfather in a digital format. He has also set up a website of the family listing its contribution in the field of art. Gian Singh tried his hand at gach (stuccowork), jarathari (mosaic work”) and tukri (cut-glass work). The tukri work, much in vogue during the Mughal rule, consists in setting pieces of glass, gold leaves or precious stones in gach work in artistic patterns.

The work of Naqqash, which was a repository of splendid paintings and murals, has suffered colossal damage with the passage of time.

Gian Singh’s son, G.S. Sohan Singh Artist, was an icon in the field of art. He was born in August 1914 and had his schooling up to the middle standard in Government High School, Amritsar. Encouraged by the popularity of his work, Artist prepared about three new designs every year, got their blocks prepared at Lahore, printed them and marketed them. He was initiated into the world of art by his father and, like his father, he turned used it for transforming Sikh religious history into delightful compositions. The walls of the Sikh museums in different parts of the world are adorned with the paintings of the Naqqash family. From 1931 to 1946, G.S. Sohan Singh Artist was doing his work, framing pictures, selling glass, Indian and foreign reproductions in bulk as well as in retail.

After the first multi-coloured design of Baba Banda Bahadur that was printed and marketed by Artist in 1932, he never looked back. He tried to translate the spiritual and worldly experiences into images through various media and techniques by using symbols, words and images in bold colours. Some of his paintings are virtually poems drawn on canvas in bold fascinating colours. These amazing paintings reveal the deeper inner spirit and the refined qualities of the artist’s skills. He has passed on this technique to his sons, Satpal Danish and. Surinder Singh, who are experts in line blocks, monochrome and tri-colour Halftone blocks, photography and painting, too.

Peculiar deed

Unbelievable but true that Naqqash once borrowed Rs 100 in 1911 from a famous book publisher in Amritsar, where he used to work to supplement his meager income, for cremation of his father, Taba Singh. The publisher got the deed signed on ‘Ashtam paper’ with conditions that would shame even the worst money-lender.

It reads, “Gian Singh’s son (G.S. Sohan Singh, a famous artist of his times) would fetch two ‘gaggars’ (big containers made of metal), full of water to their (publisher’s) house every evening, apart from 25 per cent interest till clearance of the amount.” The debt was cleared after a year.

After a gap of seven year, Naqqash again borrowed Rs 150 at a heavy rate interest of 75 per cent. In his autobiographical note, Naqqash writes with a heavy heart that he could repay the debt from the compensation of Rs 3716 that he received from the state government in lieu of the death of his son Sunder Singh in the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919. Till his death, Naqqash was under debt as he had to borrow more money for the marriage of his sister and other relatives.

Needless to say that it was the great job done by Naqqash that was later recognized the world over. The dossier sent to UNESCO for seeking World Heritage Status (though it was withdrawn by the SGPC) had made a special mention of the frescos in the interior of the Harmander Sahib. In

Interestingly, in one of his letters addressed to the then SGPC Secretary, Naqqash had expressed serious concern over the damage caused to the frescos that needed immediate attention and repair.

Last Will and Testament

The peculiar will of Gian Singh Naqqash requested all his near and dear ones not to weep after his death. The will reads, ‘Anybody who will be weeping over my death would be my greatest enemy. Instead, my well wishers should recite Satnam – Waheguru.’